Edith Kramer, the "grandmother of art therapy" died this past February in her home country, Austria, but we all gathered at NYU on a sunny Saturday in April to commemorate her life and work.

What an event it was to see my teachers and my teachers' teachers and my students, now going back almost ten years (some of whom are teaching and mentoring current students) and to feel part of the great legacy left by this tiny woman with apple cheeks and braids on her head.

The event was held at the NYU Art Therapy Department, which Edith started now some forty odd years ago. Ikuko Acosta, Program Director of the department hosted the event with Marygrace Berberian, Program Coordinator, along with help from current students and faculty.

As I like to tell my students, "You are going into a profession where you can still 'touch' those who founded it - literally." Aside from Edith many of the writers and theorists, to whom we often refer, were present in the auditorium to give testimonials, view film footage and view previously unseen photographs of Edith in her youth and throughout her life.

Psychoanalyst and art historian, Laurie Wilson, known for her biographies of sculptors Alberto Giaccometi and Louise Nevelson, helped Edith Kramer found the NYU program and was its first director. Laurie started off the program on April 26 and spoke about Edith's childhood in Vienna. Edith trained as a teenager with Friedl Dicker-Brandejs, an artist and teacher, and contemporary of Johannes Itten of the Weimar Bauhaus school. In David Henley's film "Honoring Edith" there are several quotes which seem to capture her outlook on art:

"There doesn't need to be a secret language for art."

"Making art esoteric makes it less art."

These reflect the influence of the art vs. craft debate of the early twentieth century in the Bauhaus and the Arts & Crafts movement of the 20's and 30's when the world was enmeshed in war and economic crisis. But it gave birth to a philosophy largely born of Edith Kramer's intellect that art should be a tool or avenue for healing and emotional functionality and should be accessible and not elitist. She learned what healing with art could look like from Friedl Dicker in Czech refugee camps for political prisoners and traumatized children.

Judy Rubin - the "art lady" on Mr. Roger's Neighborhood (known to many of us from childhood) is a major contributor to the field as well as an active filmmaker. It was because of her book Child Art Therapy, which I picked up at B&N many years ago, that I decided to become an art therapist.

As an art teacher in the 1950's and 60's, Judy sought out both Edith Kramer and Margaret Naumburg (the other grandmother of art therapy) because she saw that they were approaching art with children in a different way and she wanted to learn from them. Both Edith and Margaret were art educators who had some alliance with psychoanalysis. Edith was indeed born in Vienna to the social and intellectual circle of Sigmund Freud.

Judy compares Edith to Erik Erikson and Anna Freud for her clarity of intellect. Her psychoanalytic training was largely self taught, which gave her an "intellectual freedom" and originality of thought. Edith invited Judy to observe her work with blind children at The Jewish Guild for the Blind in NY and this is where Judy's education as an art therapist and career as a filmmaker seems to have been born. Judy showed footage of a young Edith working with blind children to create clay sculptures. Edith explains in the film that with the clay these children are free to express their "vision" of life without any imposition from the sighted world; giving them a sense of agency and empowerment.

David Henley, well known for his book Clayworks in Art Therapy and his work with children in the autistic spectrum, was Edith's personal assistant for several decades and said of her that, "She took so long to read my thesis that [I would look for things to fix in her studio and] I became a handyman for her." He had "literally thousands of anecdotes" about her and described her abhorrence of anything opulent, her disdain of air conditioning - "chemical air" - and her constant maxim, "The figure must be grounded," - a lesson he seems to have learned well as he has taught us all now for decades how to work with clay in a therapeutic manner. He told hilarious anecdotes of accompanying Edith to national art therapy conferences where she seemed confounded by all the formalities, which were arising in the field which she helped to found. David shared precious footage of Edith, shot by filmmaker James Pruzniak, during her last months in her New York city studio before leaving permanently for Austria.

Martha Haeseler referred to herself, and several of her classmates from the early years of the NYU art therapy program, as Edith's daughters. She and Lani Gerity and Susan Anand and Robin Goodman would accompany Edith to conferences and take care of various chores that needed doing in the program or her studio. Martha quotes Kathy Bard, who now practices in Zurich: "Edith saw us as the future and she shared the actual art she had done with clients in classes with us." Martha told us how Edith taught her students to close their eyes and feel their own face with their hands and then shape it in clay - just as her blind students at the Guild had done. I still remember standing in the darkened studio on Stuyvesant Street doing this exercise. My clay head still sits on my studio shelf as a concrete reminder of my training. Martha said Edith used to have very few teacups in her Van Dam Street studio. If she were serving tea she inevitably would have to clean one out. She told Martha, "I am married to art! What do I need with more teacups?"

I had the extraordinary experience sitting in the audience of watching Martha speak about Edith, while watching Anni Bergman (legendary child psychoanalyst and close friend of Edith's) play with her grandchild on her lap! Anni Bergman described Edith maintaining her connection to the Viennese intelligensia even while living in NY. They shared a love of hiking and Edith with visit Anni at her summer house in New Hampshire where they would hike in the mountains. "Hiking," Anni said, "conjured up anxieties about nature, about being alone and perhaps in danger," but both women found it exhilarating; the challenges of the trail being a way to find one's way in life.

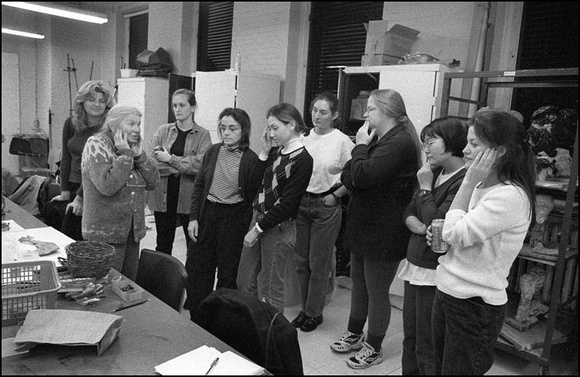

Herschel Stroyman, another lifelong friend of Edith's, brought with him from Toronto a whole lifetime of beautiful B&W photographs he had taken of her over the years. Edith with Eleanor Roosevelt at the Wiltwyck School for troubled boys in the 1950's; Edith with several of her classes from the early years at NYU, Edith in her studio and painting in nature. He described her as a "wordsmith par excellence" and spoke of her masterful article on the unity of process and product and how one cannot exist without the other.

Here is his galllery

http://herschelstroyman.zenfolio.com/p1024744045/h6DF8EFEF#h6df8efef

Lani Gerity spoke last and most eloquently of Edith as foremost a storyteller. She spoke of Edith's loft as being the "transitional space" referred to by D.W. Winnicott as the source of creativity; the place where stillness and possibility give rise to a permissiveness of original ideas - a place where original thought comes from.

She said what she learned from Edith most of all was to, "be inventive and open to the unexpected."

Here is her own tribute:

http://lanipuppetmaker.blogspot.com/2014/02/a-tribute-to-edith-kramer-1916-2014.html

The presentation was followed by a luncheon where these many generations of art therapists were able to catch up and share their favorite memories. Then NYU's Bobst Library offered a tour of the new Edith Kramer Archive organized by archivist Nancy Cricco. Here they are currently preserving her papers, original works of art from her studio and her clients, and other intellectual property. Conservation Librarian Laura McCann showed us around and gave a glimpse of the restoration process with some, by now, very well known works of art - at least to art therapists. The very drawings Edith used as examples in her seminal book Art as Therapy with Children lay before us on the tables. The archivist and her assistants handled them with gloved hands. Discussion ensued about what to do with art products made with "less than archival" materials used in classroom and school settings. Should the tape Edith presumably had placed on a drawing to repair it remain or be removed? A debate ensued among the art therapists in the room. "It should be preserved as part of the third hand technique espoused by Edith, where client and therapist sometimes act as co-creators of an object." I have paraphrased here as I do not have the direct quote nor remember who said it. During this discussion Herschel Stroyman, ever the documentarian, asked if anyone was recording the conversation for posterity. I agreed to turn on my voice-recorder. Another discussion involved whether or not researchers visiting the archive should have access to the back (or verso) of a drawing if a name was written on it. All unanimously agreed that this should not be allowed and violated patient privacy laws even if those patients were long dead and gone.

Laying on a side table was the very whale image drawn by a young boy in a small art therapy group on which Edith famously wrote about sublimation in art making. This was particularly moving to me and reminded me how effective a story teller she had been; how clearly she was able to get her point across about the importance of this image to transform a child's more aggressive urges. Yet the image created on two delicate pieces of cardboard was decaying. Laura was unsure how they were going to approach preserving it. This made me think about all the art I had made with young at-risk boys. Much of it involved things being taped or covered with glitter or other transient, fragile material. I asked Laura what the best method for preserving former client art work was. Her answer was complex and it begged the question: What is our responsibility, as art therapists, to properly archive client work that remains in our possession? The many gathered art therapists considered that the American Art Therapy Association's Ethical Guidelines do not specifically tackle this issue. With the work of the foremost founder of our field now being archived, it does seem a discussion to pursue. I agreed to type up the audio recording of this impromptu debate and write up an article for the AATA Journal to begin the dialogue.

As always, I am learning, and forever admiring of the great minds and creative spirits of the women and men in this field. We owe so much to Edith Kramer. She will be greatly missed.

The Edith Kramer Archive

http://edithkramer.com/UART%20Edith%20Kramer%20Ad.pdf

What an event it was to see my teachers and my teachers' teachers and my students, now going back almost ten years (some of whom are teaching and mentoring current students) and to feel part of the great legacy left by this tiny woman with apple cheeks and braids on her head.

The event was held at the NYU Art Therapy Department, which Edith started now some forty odd years ago. Ikuko Acosta, Program Director of the department hosted the event with Marygrace Berberian, Program Coordinator, along with help from current students and faculty.

As I like to tell my students, "You are going into a profession where you can still 'touch' those who founded it - literally." Aside from Edith many of the writers and theorists, to whom we often refer, were present in the auditorium to give testimonials, view film footage and view previously unseen photographs of Edith in her youth and throughout her life.

Psychoanalyst and art historian, Laurie Wilson, known for her biographies of sculptors Alberto Giaccometi and Louise Nevelson, helped Edith Kramer found the NYU program and was its first director. Laurie started off the program on April 26 and spoke about Edith's childhood in Vienna. Edith trained as a teenager with Friedl Dicker-Brandejs, an artist and teacher, and contemporary of Johannes Itten of the Weimar Bauhaus school. In David Henley's film "Honoring Edith" there are several quotes which seem to capture her outlook on art:

"There doesn't need to be a secret language for art."

"Making art esoteric makes it less art."

These reflect the influence of the art vs. craft debate of the early twentieth century in the Bauhaus and the Arts & Crafts movement of the 20's and 30's when the world was enmeshed in war and economic crisis. But it gave birth to a philosophy largely born of Edith Kramer's intellect that art should be a tool or avenue for healing and emotional functionality and should be accessible and not elitist. She learned what healing with art could look like from Friedl Dicker in Czech refugee camps for political prisoners and traumatized children.

Judy Rubin - the "art lady" on Mr. Roger's Neighborhood (known to many of us from childhood) is a major contributor to the field as well as an active filmmaker. It was because of her book Child Art Therapy, which I picked up at B&N many years ago, that I decided to become an art therapist.

As an art teacher in the 1950's and 60's, Judy sought out both Edith Kramer and Margaret Naumburg (the other grandmother of art therapy) because she saw that they were approaching art with children in a different way and she wanted to learn from them. Both Edith and Margaret were art educators who had some alliance with psychoanalysis. Edith was indeed born in Vienna to the social and intellectual circle of Sigmund Freud.

Judy compares Edith to Erik Erikson and Anna Freud for her clarity of intellect. Her psychoanalytic training was largely self taught, which gave her an "intellectual freedom" and originality of thought. Edith invited Judy to observe her work with blind children at The Jewish Guild for the Blind in NY and this is where Judy's education as an art therapist and career as a filmmaker seems to have been born. Judy showed footage of a young Edith working with blind children to create clay sculptures. Edith explains in the film that with the clay these children are free to express their "vision" of life without any imposition from the sighted world; giving them a sense of agency and empowerment.

David Henley, well known for his book Clayworks in Art Therapy and his work with children in the autistic spectrum, was Edith's personal assistant for several decades and said of her that, "She took so long to read my thesis that [I would look for things to fix in her studio and] I became a handyman for her." He had "literally thousands of anecdotes" about her and described her abhorrence of anything opulent, her disdain of air conditioning - "chemical air" - and her constant maxim, "The figure must be grounded," - a lesson he seems to have learned well as he has taught us all now for decades how to work with clay in a therapeutic manner. He told hilarious anecdotes of accompanying Edith to national art therapy conferences where she seemed confounded by all the formalities, which were arising in the field which she helped to found. David shared precious footage of Edith, shot by filmmaker James Pruzniak, during her last months in her New York city studio before leaving permanently for Austria.

Martha Haeseler referred to herself, and several of her classmates from the early years of the NYU art therapy program, as Edith's daughters. She and Lani Gerity and Susan Anand and Robin Goodman would accompany Edith to conferences and take care of various chores that needed doing in the program or her studio. Martha quotes Kathy Bard, who now practices in Zurich: "Edith saw us as the future and she shared the actual art she had done with clients in classes with us." Martha told us how Edith taught her students to close their eyes and feel their own face with their hands and then shape it in clay - just as her blind students at the Guild had done. I still remember standing in the darkened studio on Stuyvesant Street doing this exercise. My clay head still sits on my studio shelf as a concrete reminder of my training. Martha said Edith used to have very few teacups in her Van Dam Street studio. If she were serving tea she inevitably would have to clean one out. She told Martha, "I am married to art! What do I need with more teacups?"

I had the extraordinary experience sitting in the audience of watching Martha speak about Edith, while watching Anni Bergman (legendary child psychoanalyst and close friend of Edith's) play with her grandchild on her lap! Anni Bergman described Edith maintaining her connection to the Viennese intelligensia even while living in NY. They shared a love of hiking and Edith with visit Anni at her summer house in New Hampshire where they would hike in the mountains. "Hiking," Anni said, "conjured up anxieties about nature, about being alone and perhaps in danger," but both women found it exhilarating; the challenges of the trail being a way to find one's way in life.

Herschel Stroyman, another lifelong friend of Edith's, brought with him from Toronto a whole lifetime of beautiful B&W photographs he had taken of her over the years. Edith with Eleanor Roosevelt at the Wiltwyck School for troubled boys in the 1950's; Edith with several of her classes from the early years at NYU, Edith in her studio and painting in nature. He described her as a "wordsmith par excellence" and spoke of her masterful article on the unity of process and product and how one cannot exist without the other.

Here is his galllery

http://herschelstroyman.zenfolio.com/p1024744045/h6DF8EFEF#h6df8efef

Lani Gerity spoke last and most eloquently of Edith as foremost a storyteller. She spoke of Edith's loft as being the "transitional space" referred to by D.W. Winnicott as the source of creativity; the place where stillness and possibility give rise to a permissiveness of original ideas - a place where original thought comes from.

She said what she learned from Edith most of all was to, "be inventive and open to the unexpected."

Here is her own tribute:

http://lanipuppetmaker.blogspot.com/2014/02/a-tribute-to-edith-kramer-1916-2014.html

The presentation was followed by a luncheon where these many generations of art therapists were able to catch up and share their favorite memories. Then NYU's Bobst Library offered a tour of the new Edith Kramer Archive organized by archivist Nancy Cricco. Here they are currently preserving her papers, original works of art from her studio and her clients, and other intellectual property. Conservation Librarian Laura McCann showed us around and gave a glimpse of the restoration process with some, by now, very well known works of art - at least to art therapists. The very drawings Edith used as examples in her seminal book Art as Therapy with Children lay before us on the tables. The archivist and her assistants handled them with gloved hands. Discussion ensued about what to do with art products made with "less than archival" materials used in classroom and school settings. Should the tape Edith presumably had placed on a drawing to repair it remain or be removed? A debate ensued among the art therapists in the room. "It should be preserved as part of the third hand technique espoused by Edith, where client and therapist sometimes act as co-creators of an object." I have paraphrased here as I do not have the direct quote nor remember who said it. During this discussion Herschel Stroyman, ever the documentarian, asked if anyone was recording the conversation for posterity. I agreed to turn on my voice-recorder. Another discussion involved whether or not researchers visiting the archive should have access to the back (or verso) of a drawing if a name was written on it. All unanimously agreed that this should not be allowed and violated patient privacy laws even if those patients were long dead and gone.

Laying on a side table was the very whale image drawn by a young boy in a small art therapy group on which Edith famously wrote about sublimation in art making. This was particularly moving to me and reminded me how effective a story teller she had been; how clearly she was able to get her point across about the importance of this image to transform a child's more aggressive urges. Yet the image created on two delicate pieces of cardboard was decaying. Laura was unsure how they were going to approach preserving it. This made me think about all the art I had made with young at-risk boys. Much of it involved things being taped or covered with glitter or other transient, fragile material. I asked Laura what the best method for preserving former client art work was. Her answer was complex and it begged the question: What is our responsibility, as art therapists, to properly archive client work that remains in our possession? The many gathered art therapists considered that the American Art Therapy Association's Ethical Guidelines do not specifically tackle this issue. With the work of the foremost founder of our field now being archived, it does seem a discussion to pursue. I agreed to type up the audio recording of this impromptu debate and write up an article for the AATA Journal to begin the dialogue.

As always, I am learning, and forever admiring of the great minds and creative spirits of the women and men in this field. We owe so much to Edith Kramer. She will be greatly missed.

The Edith Kramer Archive

http://edithkramer.com/UART%20Edith%20Kramer%20Ad.pdf

RSS Feed

RSS Feed